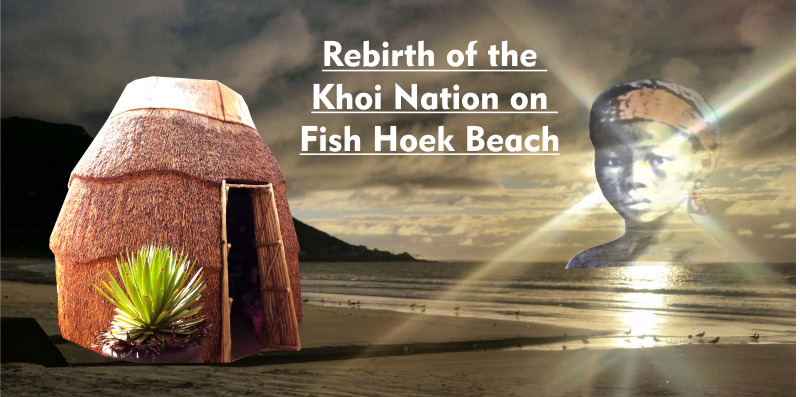

As custodians of Khoi culture, we are proud that our Khoi hut is part of the Cape South Peninsula Heritage Route, 366 years after all huts were removed by the Dutch in the Cape.

Little was known of the first inhabitants of the Cape Peninsula, the Strandlopers.

The KhoiSan (first recorded as Koïsan) genetic profile is so ancient and so distinct,

that no other human group bears the same DNA.

KROTOA,

KROTOA,

Mother of the First Nation

Known as Eva to the Dutch and English settlers, Krotoa was the niece of Autshumao, a Khoi leader and interpreter (called Harry or ‘Herry’). Krotoa worked as a servant to Jan van Riebeek’s wife Maria and was taught Dutch, Portuguese and Christianity. She established herself as a staunch friend of the Dutch and was later instrumental in working out terms for ending the First Dutch-Khoi-khoi War. Her marriage to Danish soldier and explorer Pieter van Meerhof was the first recorded union between a ‘native’ and a ‘settler’. Later Krotoa was banished to Robben Island where she died on 29 July 1674.

Rebirth of the Khoi Nation on Fish Hoek Beach

When the first Dutch settlers arrived at the Cape in 1652, they brought with them

a culture completely foreign to the KhoiSan who functioned as a tribal unit.

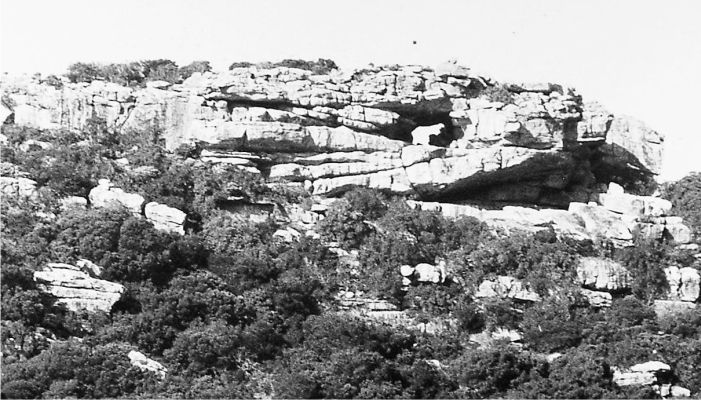

Peers Cave

In 1920 when Victor and Bertie Peers uncovered a midden of over one metre thick and several thousand years old, at what was later to be known as Peers Cave, they did much to help us understand the life of the early inhabitants of Fish Hoek. The remains of four adults and four children were found at various levels, but it was the lone skull of a male, aged thirty years and reliably dated at near to twelve thousand years that brought the world’s attention to their work. Known as The Fish Hoek Man the skull at that time, 1929, was described as ‘the largest-brained type of man so far discovered’.

Peers Cave is in fact a rock-shelter, the only one of its kind in the valley. It is 123 metres above sea-level, with a 30 metre entrance under a projecting rock of 3.7 metres from the floor and 13 metres to the back wall. It is south-facing and is protected from the prevailing north-west and south-east winds. The floor consists of a black powdery soil built up of decayed vegetables and animal matter such as sea-shells, wood-ash, bones and rock fragments. Materials were always brought in to the shelter, but little was removed. This accounted for the great depths of the deposits. Besides the human remains, ostrich eggshell beads, shell pendants, remains of small skinbags, pieces of mother of pearl and stone tools were found. A separate section of the cave was used for the making of tools and spearheads.

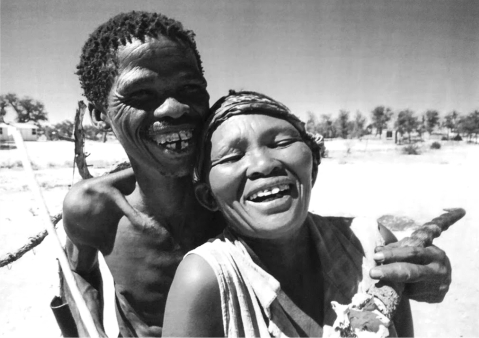

The inhabitants were early Khoisan hunters as against herders. They exploited the marine resources of the coast and included in their diet were seashells and mussels, as well as fish caught in fish-traps on the receding tide. They were tribal and unlike the nomadic herders were more settled in their existence. The majority of these chocolate-brown folk were under five foot in height and had small black tufts of hair on their scalps.

The men were astute hunters, very agile and skilled with spears and poisoned arrows. They hunted in groups of five to ten and carried skinbags slung over their shoulders.

The bags contained tools for skinning and foraging. Water in the Fish Hoek Valley was plentiful, not only in the Silvermine River but also in the many lagoons where birdlife abounded and formed part of their diet. The remains of large buck in the form of shattered shin bones (for the marrow inside) and teeth were unearthed at the cave which indicates the plentiful supply of kudu and eland in and around Fish Hoek Valley. The womenfolk cared for children, and collected wood as well as shellfish and mussels.

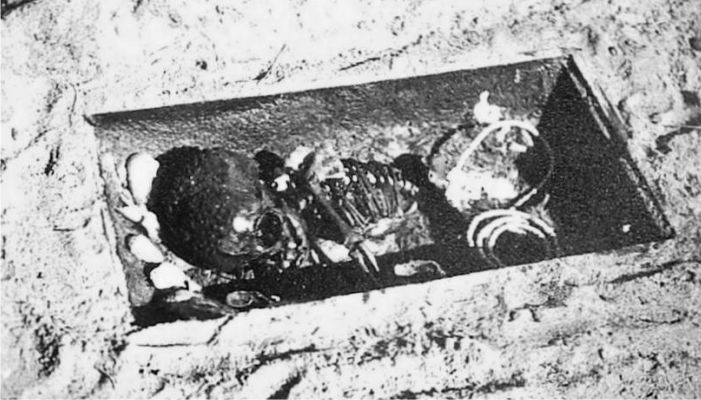

The burial of the bodies in the cave was in the sheltered area near to where the Khoisan slept, and it seemed to have been in their culture to bury the dead near the sleeping area where they could maintain custody over the departed. Three of the adult skeletons uncovered showed death by violence, probably in the plains down below and brought up to the shelter for burial by family members and friends. No burial stones were evident in the cave, but the custom was to place a flat stone over the head and shoulders of the deceased.

The presence of various artefacts when unearthing the skeletons revealed an interesting insight into Khoisan culture. The first skeleton, that of an infant, had been rolled in buckskin and placed in a bed of leaves. A string of conus shells with cut edges for stringing (a substitute for today’s baby’s rattle) was found alongside the skeleton as well as three strings of ostrich eggshell beads which were placed around the infant’s neck.

The second skeleton, that of a young woman aged eighteen to twenty (her wisdom teeth had just matured) was accompanied by an outstanding display of bead-work. Strings of thousands of beads were wrapped around her limbs and waist and below her knees were bands of beautifully-worked patterns of ostrich eggshell beads to which were added many strips of wooden beads which were fitted in long strings against each other in a ball and socket arrangement. Around the young woman’s neck and shoulders was another necklace consisting of nine prepared skin bags, sausage-shaped, with carefully pleated ends sown up. These were strung together on a thick twist of animal sinew at equal distances from each other. Other items around the skeleton were three pieces of yellow oxide, two pieces of bright red oxide, a flaked stone knife and various other pebbles and stones.

On close examination of the skeleton it was found that the methodical and elaborate burial was undoubtedly for a young woman who was born a cripple. This was determined where three vertebrae proved defective and the supporting arm-projection on the one side of each was missing.

The result would be a lessening of the leg by 75mm. The young woman therefore must have been delicate and was looked upon with reverence and sympathy by the rest of the tribe. Her bead-work was different from the other womenfolk. This was done hopefully to distract any other repetitions of deformancy in the tribe as a cripple must have been a severe handicap to a foraging people. What does all this tell us of these people? They were superstitious, caring (they did not kill the young woman as a child), had family values and were a closely knit unit. Life expectancy was between forty to fifty years and this was further reduced when European diseases such as tuberculosis and smallpox decimated their numbers.

What does all this tell us of these people? They were superstitious, caring (they did not kill the young woman as a child), had family values and were a closely knit unit. Life expectancy was between forty to fifty years and this was further reduced when European diseases such as tuberculosis and smallpox decimated their numbers.

Their culture excluded the concept of ‘yours’ and ‘mine’ and everything belonged to everyone, the earth and its fruits were for all to have. This lead to stealing and constant clashes with the new European settlers and resulted in their virtual extermination but for those who fled to the inhospitable terrain of the Northern Cape.

Peers Cave gives us an in-depth look at the life of the early inhabitants of Fish Hoek, but the sad fact is that it never received the accolades it deserved for it was in fact excavated too early by those with little experience. Had it remained uncovered until archaeology was more advanced and well established in South Africa, it would have probably been a world renowned site.

~ The Far South by Michael Walker